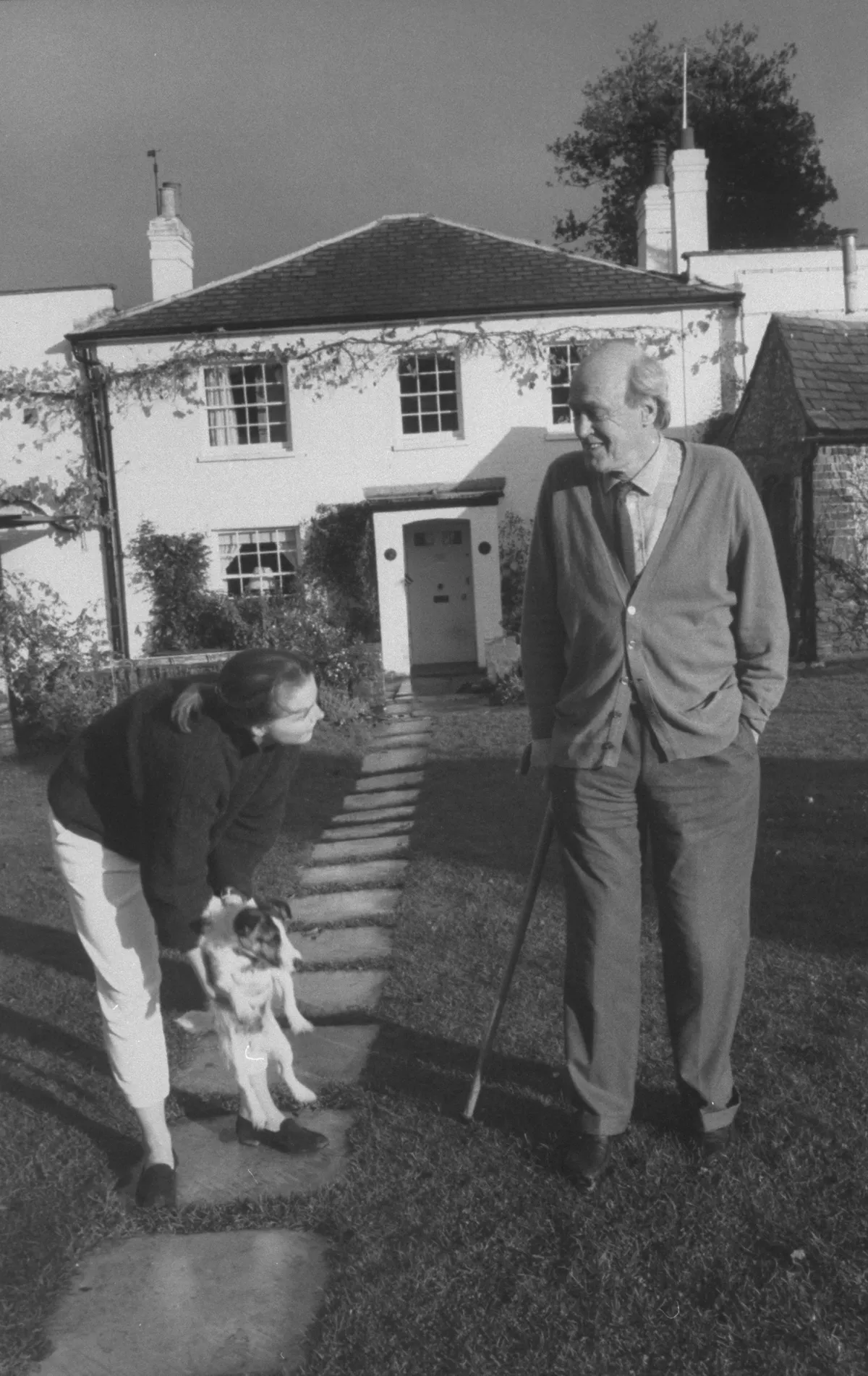

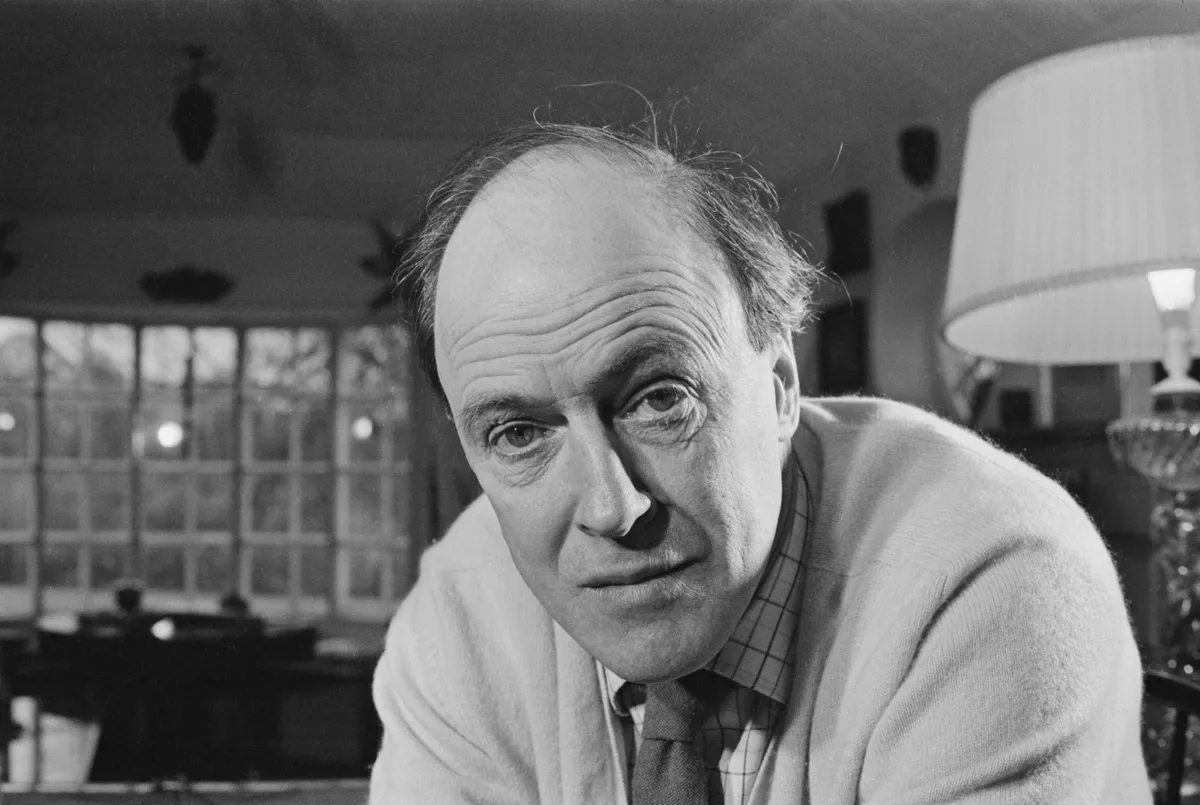

“You could always tell when Roald had been pottering in the garden,” recalls Felicity Dahl. “He would leave piles of prunings about the place.” For Roald Dahl, best-selling author, poet and champion onion grower, who died in 1990, the garden at Gipsy House in Buckinghamshire was a necessary respite from his work. “It was Roald’s sanctuary; it was somewhere for his own personal thoughts,” says Felicity – who is also known as Liccy. “He loved the plants and their scent and would walk around the garden most days – if he saw something that needed doing he would just do it.”

When Roald arrived at Gipsy House in 1954, it was a modest farmhouse enveloped in one acre of blank canvas on a gentle north-south slope and framed by captivating views of the Buckinghamshire countryside. Yet for a long time after he moved in, caring for his family was Roald’s sole concern and the garden fell by the wayside. “By the time Roald and I were married in 1983, the garden was in a poor state,” explains Liccy, who was Roald’s second wife, so she decided to formulate a rescue plan. “It was very exposed, so my priority was to divide the space into a series of rooms to create shelter,” she says. “To start with, we called in a garden designer but then chose to do our own thing.” And with that Liccy, Roald and head gardener Keith Pounder began to implement her plan bit by bit.

Roald competed every year against local tradesmen in a bid to grow the largest onions. He always won. He always cheated.

It started with the delightful kitchen garden. At the top end of the garden, but separated from the ornamental areas by a small car park, 3.5m-high red brick walls were built for shelter, while the slope was terraced to accommodate raised borders of railway sleepers. A glasshouse copied from nearby Tythrop Park houses a vine, nectarines and peaches; the garden’s walls support fan-trained apples and pears. “I was determined to have old-fashioned fruit with good flavour,” Liccy says. “Roald took great care in sourcing plants so our fruit came from the best stock.” What Roald loved most of all, however, was growing vegetables. Where onions were concerned he was obsessed. He grew two cultivars, ‘Robinson’s Mammoth’ and ‘Robinson’s Red Mammoth’, and competed every year against local tradesmen in a bid to grow the largest. He always won. “He always cheated,” laughs Keith Pounder. “Instead of growing them from seed like everyone else he gave himself a head start by buying in seedlings.”

On the opposite side of the car park, the ornamental gardens are approached through a thick windproof yew hedge, which is repeated throughout much of the garden, enclosing each room. Here the formal potager was established on the site of the original vegetable garden, opposite a greenhouse that once housed Roald’s prize-winning orchids. “Roald got bored with the orchids and gave them away,” explains Liccy. “We took the greenhouse down and Keith designed and built the potager in its place.” The planting scheme of hot reds and moody purples is edged with box and punctuated by four mature Quercus ilex trees trimmed into lollipops. At the edge of the garden stands an Aspen tree (Populus tremula) chosen by Roald’s sister Alf for the evocative trembling of its leaves in the wind. However, now that the trees have reached maturity, the garden needs rethinking. “The potager was originally designed as a sunny garden,” says Keith, “so we are having to adapt the planting to suit shady conditions.”

You might also like

On the edge of the garden sits Roald’s writing hut. An unpretentious, whitewashed outhouse, inspired by Dillon Thomas’ writing hut, the front door is painted bright yellow, Roald’s favourite colour. It is as integral to the garden as any of Liccy’s rooms, but when the garden was in its infancy the hut stood solitary and exposed, linked to the rest of the landscape only by a concrete path. In 1984, Roald and Liccy planted an avenue of pleached limes along the path. “Every time Roald walked to and from his writing hut, it gave him great satisfaction to pleach a bit of the avenue,” Liccy says.

Surprisingly, the garden rarely inspired Roald’s work; the blinds of the hut were firmly closed as he wrote, shielding him from distractions. Nevertheless, one or two characters did spring from the garden. In the orchard, a gipsy show van stands resplendent in a livery of bubblegum pink and sky blue: Danny Champion of the World just happens to live in a similar van. And the ancient cherry tree outside the kitchen garden appears incognito in James and the Giant Peach as the peach tree. Other features in the garden could have leapt from the pages of any one of Roald’s tales. A Russian vine has invaded the shed roof with such ferocity that it has become the roof – the shed now goes by the name of the hairy shed. There are also some deliberate but subtle references to Roald’s work. In the white garden, where generous borders are planted with white herbaceous plants and shrubs, an octagonal birdhouse is filled with enormous, voluptuous glass jars, bought by Liccy at auction, and which could only belong to the BFG.

It is the sunken garden that gives Liccy her greatest pleasure. Taking advantage of necessary repairs to the garden’s boundary wall and the bottom end of the slope nearest the house, Liccy and Keith designed an area of octagonal lawn sunk into raised brick borders planted with yellow-flowering plants. The gentle trickle of water from a wall-mounted fountain in harmony with the wind in the trees, lends the sunken garden a unique atmosphere. “I especially love it when it’s bathed in evening light,” Liccy remarks.

In less sensitive hands, the garden at Gipsy House could have become a miniature theme park, or set in aspic. Instead, Liccy and Keith have struck the perfect balance. “The garden has been developed very much with Roald in mind, but it is always evolving,” says Liccy. Together she and Keith are still following her plan. In the next phase they will tackle the tired herbaceous borders on the east side of the house by dramatically increasing their width and replanting with shrubs and perennials in a lavender and pink colour scheme.

Beside Roald Dahl’s writing hut there is a simple rectangular space enclosed by a yew hedge. Inside, a maze of 30cm-high box shelters beneath the canopies of 19 whitebeams (Sorbus aria). The maze is paved with York stone slabs carved with quotations from Roald’s books, each chosen by a family member or close friend. The spirit of the place is deeply moving. “The maze is the only area made as a memorial to Roald,” says Liccy, “but like the rest of the garden it was made for sharing and to inspire. If Roald could see it all now I think he would have a smile on his face.” And for a moment the wind rustles the leaves of the whitebeams, just as if Roald’s spirit is echoing Liccy’s sentiments.

Gipsy House and Roald Dahl's garden in Buckinghamshire is not open to the public. The Roald Dahl Museum is in Great Missenden and is open every day except Monday. See the website for more information on opening times.