In my tiny, urban, outdoor space, there are almost as many plants in pots as there are in the ground. Small trees grow in terracotta, wallflowers and foxgloves in verdigris- patinated copper planters, and woody-stemmed herbs in zinc troughs.

There are azaleas and conifers on the roof in large plastic pots, heavy enough not to blow away, but light enough not to do any structural damage. There are even a few with vegetables in. This garden would be less beautiful and less productive without its rows of earth-coloured pots.

You may also like:

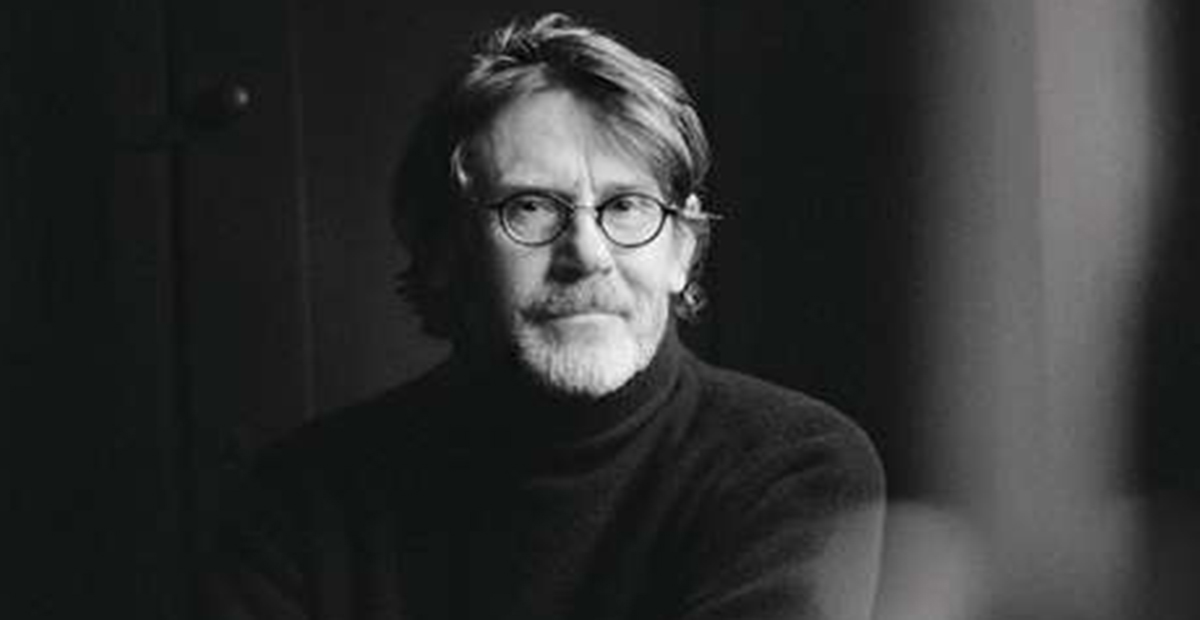

- Nigel Slater is open to temptation from the plant catalogues

- The big job Nigel Slater is embarking on this year

- Nigel Slater on planting failures

- Nigel Slater on the joy of sitting in his garden

I have to admit to a love bordering on obsession with old, chipped terracotta, especially for cherished, ancient pelargoniums. The rust-red clay seems to flatter the deep reds and pale-pink petals of Pelargonium ‘Lord Bute’ and P. ‘Madame Auguste Nonin’.

Of course, I’m not the only one who feels they were made for one another, and Victorian pots now fetch a high price. The days of reclamation yards full of stacked pots going for a song seems to be a thing of the past.

In late spring and early summer, I start my dahlias off in plastic tubs before transferring them to the terracotta planters vacated by narcissi and tulips. The design, wide with several horizontal bands,

is based on a Mediterranean olive-pressing barrel.

The ugly plastic versions are kept for years, and while I would never buy one, I have to admit they are easy to stack when not in use, coming out year after year. (Whisper it, but I often find such pots more practical, as the soil stays moist for longer – no thirsty clay to drink the water up.)

Worst of all is the pot that kills everything: the mysterious monster in which nothing will survive for more than a year.

The introduction of pots and planters to this space was not purely aesthetic. There was more to it than that. From the outset, I realised that this house was built on heavy London clay. In digging what seemed like tonnes of organic matter into this impenetrable medium beneath my feet, I had lightened the soil to a fairly friable tilth the texture of chocolate cake. Good for roses and hydrangeas, potatoes and beans, and indeed pretty much everything I planted.

Then came the rub. Year after year, my thyme refused to overwinter. Lemon verbena dried to a crisp stick. Time and again my tarragon plants failed. Lavender and rosemary gave up the ghost within weeks of being planted. I spoke to the queen of herbs, Jekka McVicar, who, without even seeing it, knew my soil was the culprit. The roots were getting waterlogged in my richly composted soil. They needed to drain, not sit and marinate over winter.

I followed Jekka’s suggestion that I should plant my herbs in pots, using a lighter, grittier soil than in the garden. A few lemon thymes aside, for the most part they have not only survived, but thrived. Indeed, a rather stately rosemary she gave to me is now knocking on for a decade old, proudly sitting outside the kitchen door.

The introduction of pots and planters to this space was not purely aesthetic. There was more to it than that.

It is the same with tomatoes and dahlias, whose insatiable hunger for nutrients and water would make most garden shrubs feel a little queasy. Living in pots and planters, they can feast on as much tomato food as they like, or as much I remember to give them.

There have been disasters. The hideously expensive Italian pot that was hit by a stone ball falling from its plinth. (I repaired the pot with wire, but it is, nevertheless, fragile and unmovable.) There was also a tall, conical number that wobbled on an uneven path and crashed to its death. Like others, it gets a second life as crocks in the bottom of others. Worst of all is the pot that kills everything: the mysterious monster in which nothing will survive for more than a year. We call it the poisoned pot. Right now, it is home to a large and, as yet, unkillable fern.

The control one has over plants in pots extends beyond the growing medium. Not only can I give them the correct amount of water, but I can also move them around the garden according to the weather. A pot of basil, the most capricious of potted herbs, can follow the progress of the sun, as can a potted aubergine that needs the hottest wall in the garden if it is to turn into anything resembling the black beauty on the seed packet.

Growing in pots has also allowed me to control my rampant mint, fraises de bois and Jerusalem artichokes. Only a practical joker could ever want more than a few artichoke plants – they are the gift that keeps on giving – but you can control their spread when grown in a hefty planter. The kind reader who once sent me a batch of wild strawberry plants, which then colonised my garden, is looked upon more fondly now I have discovered that growing them in a pots keeps their marauding habits more easily under control.

There is always a downside to everything, and that includes my beloved pot collection. Small ones tend to dry out too quickly and large ones, the sort that cost the price of a month’s mortgage, are almost impossible to keep watered. Two weeks of endless rain and the soil around your trimmed bushes will still be as dry as a Farley’s Rusk. I learned this the expensive way, assuming that the heavens had done the watering for me.

As we explored the contents of the pot for mites or fungal infections the truth became plain – they simply needed watering. A million raindrops had simply bounced off the leaves and never got down into the compost. Lesson learned.

Such impracticalities are combated by the ease with which you can make a dazzling display – think of the porch at Great Dixter – or the joy of seeing a single rare snowdrop emerge from a tiny, weather- beaten pot, and hang its green-and-white head like a precious jewel. And although I have yet to be bitten by the auricula bug, I’m on the lookout for some particularly beautiful old pots, just in case.