Conifer forests cover large swathes of Scotland and are a common sight in most of our British woodlands. They are impressive-looking trees and they evoke a sense of mystery and fairytale when you walk amongst them. Here, Lia Leendertz takes a closer look at the Scots Pine, Yew and Larch.

Here's how to identify pine, yew and larch trees

Pinus sylvestris - Scots pine

Scots pine is the national tree of Scotland, and it is in Scotland that you will see it at its finest, in ancient pine forests and in majestic stands on heathland. Its leaning, red trunks glow in the low, northern light, and its spacious, gappy canopy is never dense enough to create a dark and gloomy forest floor. All of those found in England, Wales and Ireland have been planted or have naturalised from plantings – even those of the New Forest, where it looks so at home, were only introduced in the 1600s. It followed hard on the heels of the retreating glaciers at the end of the ice age, settling in the far north of the UK and carrying on beyond, well into the Arctic Circle. This quick, post-ice age settlement makes it one of our oldest natives, as well as being one of only three native conifers.

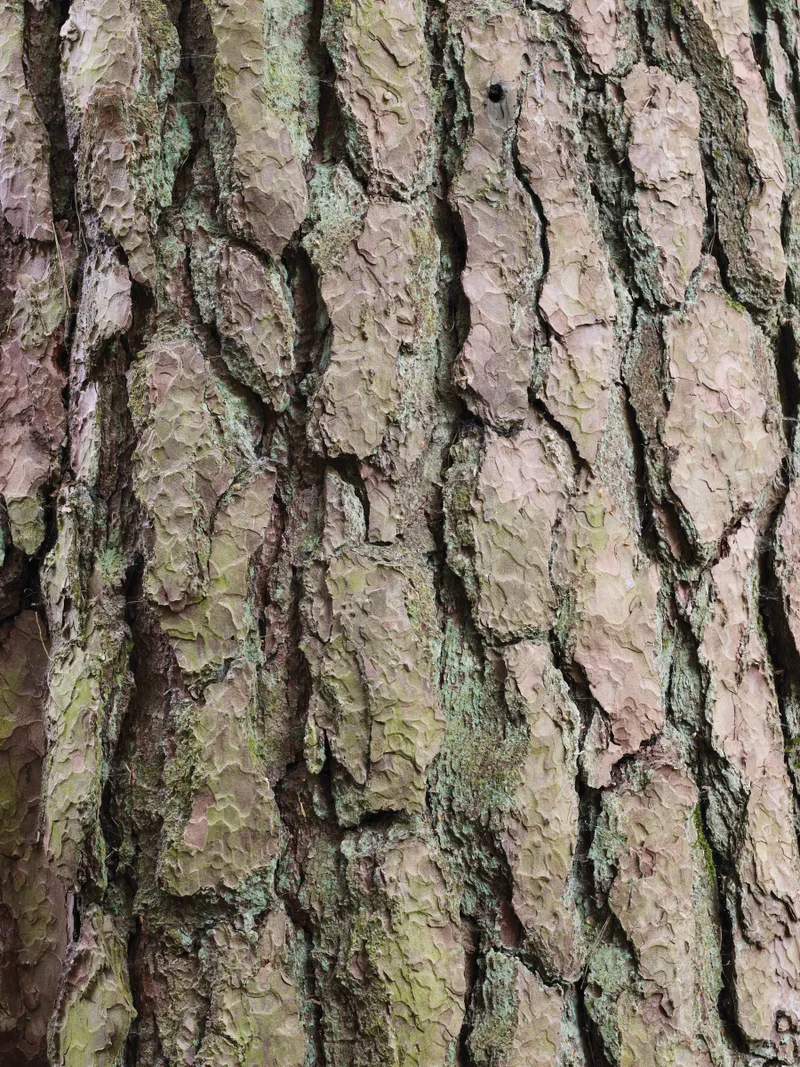

Bark

The bark is flaky and reddish brown towards the crown of the tree and darker brown and covered in shiny scales towards the base.Buds

Clusters of waxy brown buds can be found at the tips of the branches. Female flowers, which are small, round and red, are borne at the tips, while male yellow flowers are further down the branch.Needles

Pine needles are long and soft with a twist, and are borne in pairs. They are glaucous bluey green in summer and darker green in winter – just perfect for your Christmas wreath.Cones

Young cones are bright green with a brown raised dot at the tip of each scale, and over time the whole cone turns woody and brown.Silhouette

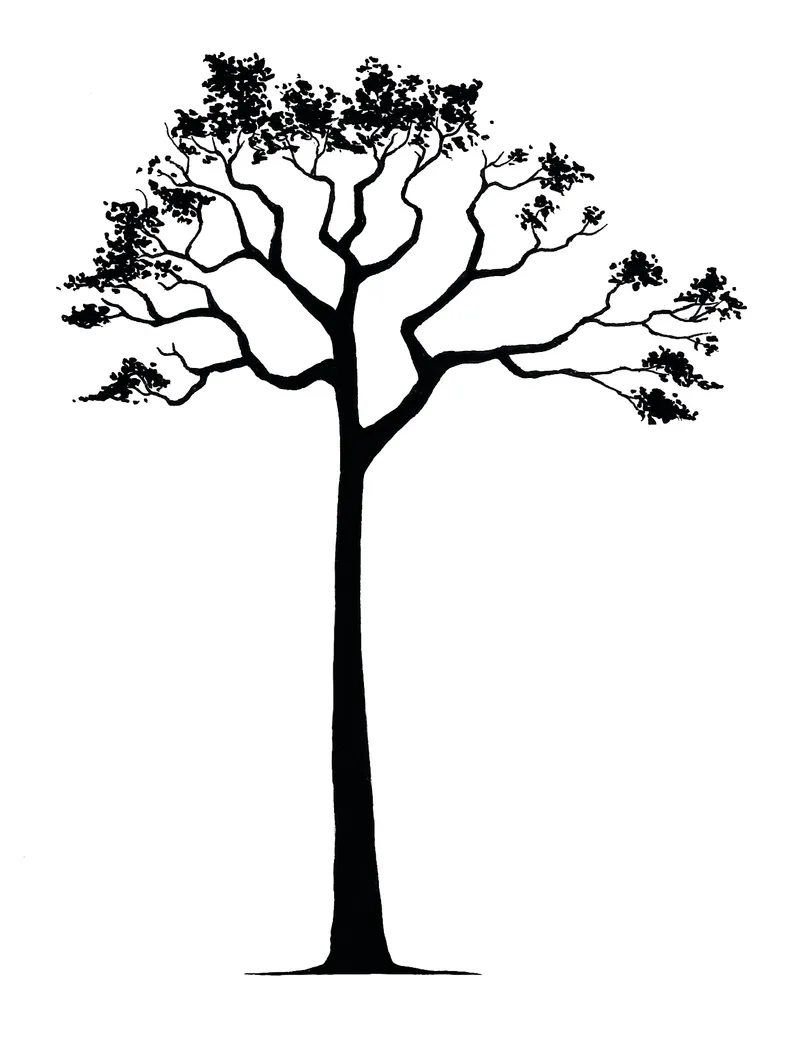

Scots pines are tall, towering trees. Their elegant trunks have very few lower limbs and often lean to one side. Scots pines always look top heavy, holding a dome of foliage high in the air.

Read more on...

Identifying Taxus baccata - yew

Dark and brooding yews are incredibly long lived – one known as the Fortingall Yew in Perthshire is dated between 2,000 and 3,000 years old. Perhaps it is their longevity and the seeming permanence they have in the landscape, as well as their sombre nature, that has seen them associated with both death and immortality, and they are often found in churchyards. As they age their lower limbs take root and the original tree hollows out, so a really ancient tree can become a thicket, and then a ring. Yew timber is highly prized because of the contrast between the creamy white sap wood on the outside of the tree and red-brown twirling heartwood. Determinedly continuing its deathly theme, every part of the plant is toxic, except for the red flesh surrounding the (toxic) seeds. It is native and can be found naturally occurring on chalk in southeast England and limestone in the north and in shady oak woodland.

Bark

Thin bark is rich reddish brown in colour and scaly, and becomes deeply and characterfully ridged and furrowed with age. The tree often hollows out from the inside.Needles

Broad, flat, dark green and relatively widely spaced, with

a point. Usually arranged in two rows on either side of the stem, but on upright growth they will spiral around the stem.Red fruits

Female trees produce bright-red fruits. The fleshy red aril, or seed covering, is the only part of the tree that is not toxic, although the seed within it is. Birds pass the seed undigested.Silhouette

Dense, broad and low-growing trees with many low-lying branches that often touch the ground and can mean that some mature specimens make excellent climbing trees.

Identifying Larix decidua - European larch

As one of the few deciduous conifers the European larch is an oddity. Its foliage turns yellow in autumn and drops while that of most of the other conifers stays resolutely dark green and clings to the branches. This makes larches softer and more feathery-looking than most conifers, and makes their forests gentler places too. The falling needles create a rich and hospitable mulch beneath the trees, which, combined with the increased light levels, allow for a pretty and varied understorey of bluebells and forest shrubs that would never be found under the dense and dark canopy of most conifer forests. Larches are native to the mountains of central Europe and not native to Britain. However, they are found in huge swathes in Scottish plantations, where they were planted in vast number in the 1800s for timber and for reforestation. You will also see them in parks and gardens.

Bark

Pinky brown to pale brown in colour, and developing fissures and knobbly plates with age. Twigs have a golden and pinky colour that glows in winter sunshine.Needles

The bright-green soft and flattened needles are bunched together and arranged radially in tufty whorls attached all along the stems by woody nubs.Cones

Short, oval-shaped cones emerge green in the summer and then slowly turn woody and brown towards autumn – just as the foliage is turning yellow.Autumn colour

Needles emerge bright green in spring, turn butter yellow in autumn and drop in winter.Silhouette

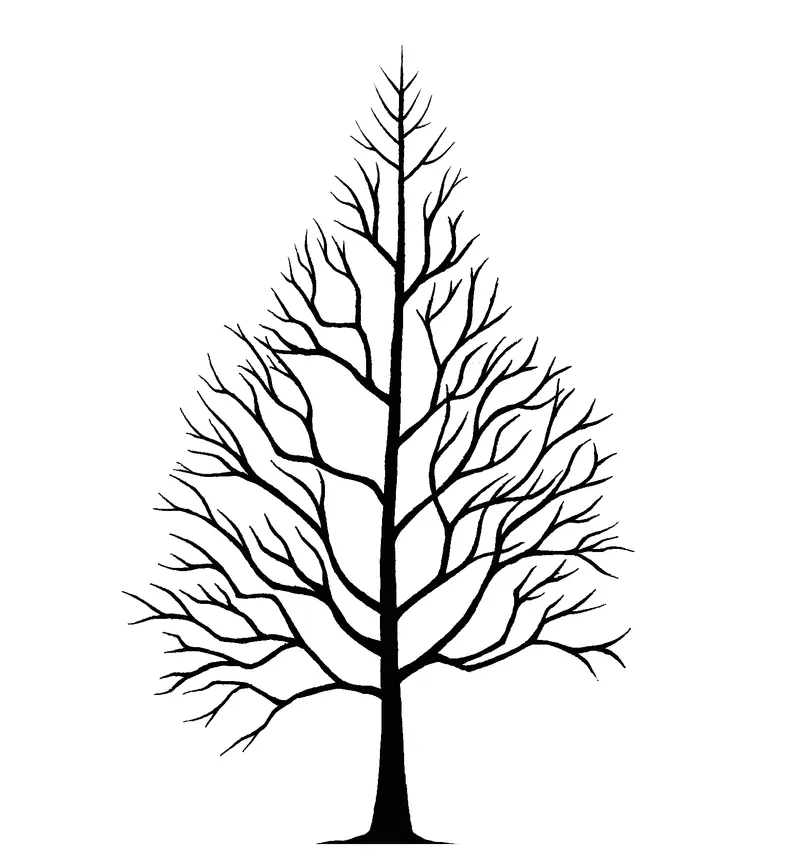

When young, its upwards sweeping branches give the larch a classic coniferous cone shape that becomes broader over time.

Words Lia Leendertz

Photos Jason Ingram

Illustration Liam McAuley